The Blue Tablecloths of Georgia: New Life of an Old Tradition

In the past, textile production held a special place in the country of Georgia’s arts and culture. The oldest samples date back to around the end of the seventeenth century, cotton tablecloths painted in various hues of blue. In the eighteenth century, artisans began creating printed textiles, using woodblocks with decorative engravings. The method of “cold vat dyeing,” which originated in the East, spread widely in Georgia in those times.

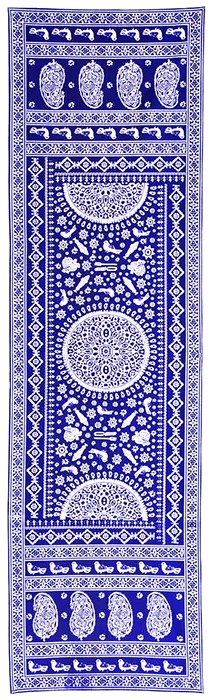

These textiles were colored blue using indigo paint, obtained as a result of processing of the indigo plant. The specific character of the patterns and, most importantly, the color, made Georgian textiles different from their Russian and European counterparts. These products are known as lurji supra, the “blue tablecloths.”

In order to preserve a pattern and prepare the textiles for cold dyeing, artisans of this technique mix wax with fat and apply it to the cloth using a woodblock. The pattern depends on the craftsmen, who create compositions based on specific themes, at his sole discretion. The elements of such patterns include the rosettes and medallions, commonly arranged in the center, plus floral and geometric ornaments decorating the borders.

Georgian artists enriched the compositions with the figures of women and men in national costumes, flora, fauna, household items, and more. Although the blue tablecloths are used in daily life, images of musicians, dancers, warriors, and crosses reflect their ceremonial application, such as ornaments for wedding feasts, religious holidays, and royal hunting feasts.

Factory manufacturing of printed textiles began in Georgia at the end of the nineteenth century, gradually driving out traditional hand-painting methods. In silkscreen printing, various patterns modeled after the blue tablecloth designs could be “burned” onto special fabric tightly stretched over a frame. Paint is applied through the screen, coloring only the negative space of the design onto the textile—a process far more efficient than woodblock printing.

In extract (discharge) printing, a blue textile is treated with a special chemical mixture. When Rongalite (sulphoxylat formaldehyde) is applied through a prepared silkscreen, the pattern turns white under its effect. Since this technique requires a special storage area, it is used only in factories.

The blue tablecloths produced by Georgian factories in the twentieth century become an aesthetic symbol of the country. As the screen-printing technique improved, production grew and met increasing market demand from both tourists and locals.

But at the end of twentieth century plants and factories in the cities of Georgia closed as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and great political changes. Production of blue tablecloths stopped. For years artisans discussed how to restore the art form.

In 2010, despite the fact that the country could still not reopen plants and factories, the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts launched a research laboratory named Lurji Supra to study the now century-old blue tablecloths. Founders Tinatin Kldiashvili and Ketevan Kavtaradze, design professors at the academy, focused on restoring the original, long-forgotten textile technology of the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

Their research and trials lasted for over a year. They borrowed patterns from wall paintings, ancient manuscripts, and figurines from the Bronze Age. They experimented with screen-printing on other articles, such as napkins, aprons, bag, and head scarves. In 2011, they presented their work to great public interest, and soon began selling textiles from the laboratory and art galleries.

Since then, the students have represented Georgia and shared their work at the Strasbourg Christmas Market, the Artigiano in Fiera international craft fair in Milan, and the Art Schools of the World – Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Art exhibition in Florence. The laboratory has been so successful that textile printing using various methods and technologies has since regained popularity in Georgia and abroad.

Today the Lurji Supra lab contributes to the reconstruction, preservation, and development of this traditional field, this piece of intangible cultural heritage. Students are able to use old motifs and create their own design, which the founders believe is very important for sustaining living traditions. Their active involvement in the working process now makes it possible to pass the knowledge from generation to generation.

Nana Meparishvili was a Carnegie research fellow at the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage and is a Ph.D. candidate at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University in Georgia.

Tinatin Kldiashvili is a professor and dean at the Faculty of Design, Tbilisi State Academy of Arts, and Ketevan Kavtaradze is the academy’s associate professor and holder of an authorized license to produce the blue tablecloths. All images are courtesy of their laboratory, Lurji Supra.

Source: Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage